Exercise, Aging, and Weight Loss in High Perspective (above)

Exercise, Aging, and Weight Loss in High Perspective (above)

Do you exercise? Do you exercise well? Are you successful at losing weight? When we think about it sometimes, exercise is a peculiar topic: lots of people do it, everyone talks about it, countless experts teach you how to do it - and yet to this day, we still don’t have a consensus on it. There are so many different ways of talking about exercise that there are all kinds of schools of thought, one tutorial today, one secret tomorrow, and I don’t know which one is right.

This is of course because the human body is complex, the occasional success story may not be of generalizable value, and there are many issues that have not been clarified. I’ve written specifically before that nutrition is the most unreliable study, and that research conclusions are often reversed. Granted, scientists can’t be said to be ignorant about exercise. In fact there are now some very hard conclusions that just haven’t caught on yet.

Daniel Lieberman, a human evolutionary biologist at Harvard University, recently came out with a book called Exercised: Why Something We Never Evolved to Do Is Healthy and Rewarding (English edition 2021; Chinese edition, Zhanlu Culture. 2022), I read it and was very inspired, and I feel that the chain of logic is now clearer.

With the help of Lieberman’s book, let’s talk about exercise, aging and weight loss from a high point of view.

In this talk, I’m going to say one insight, one piece of good news and two pieces of bad news.

✵

Exercise is first and foremost about being healthy, but what kind of shape is healthy? A 24-year-old young man, the last year has been delivery, every day walking the streets sometimes have to climb the stairs, come home just want to rest. A 48-year-old middle-aged man, no disease, just a little obese, often feel less energetic. A 72-year-old old man, body shape to maintain a very good, very focus on dieting, but feel that they are too old, do not dare to exercise.

Are they healthy? Should they exercise? How does this account work when it seems that different ages should be held to different standards?

Lieberman argues that whether you are healthy or not, whether you should exercise or not, you shouldn’t be comparing yourself to whatever the standards are for modern people - perhaps most modern people are ‘not normal’. You should compare yourself to those hunter-gatherers of the Paleolithic.

Hunting and gathering is a way of life that humans have used for at least 1.8 million years. Agriculture didn’t come into existence until 10,000 years ago, industry only came into existence two hundred years ago, and office white-collar jobs have only become commonplace in the last few decades. Our bodies are a product of evolution, and that environment to which evolution adapted was primarily a hunter-gatherer environment.

- Simply put, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle determines the factory settings of our bodies. *

If your body was designed to let you walk around every day, and sometimes run for a while, so that you can live and move until you are old; but your life is to sit in an office all day, with little exercise, and also to do nothing once you retire - isn’t that a bit of a mismatch?

Luckily for researchers like Lieberman, there are still some primitive tribes in the world that live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The researchers compared their age-specific body metrics to those of us who live modern lives, and the results are startling, to say the least.

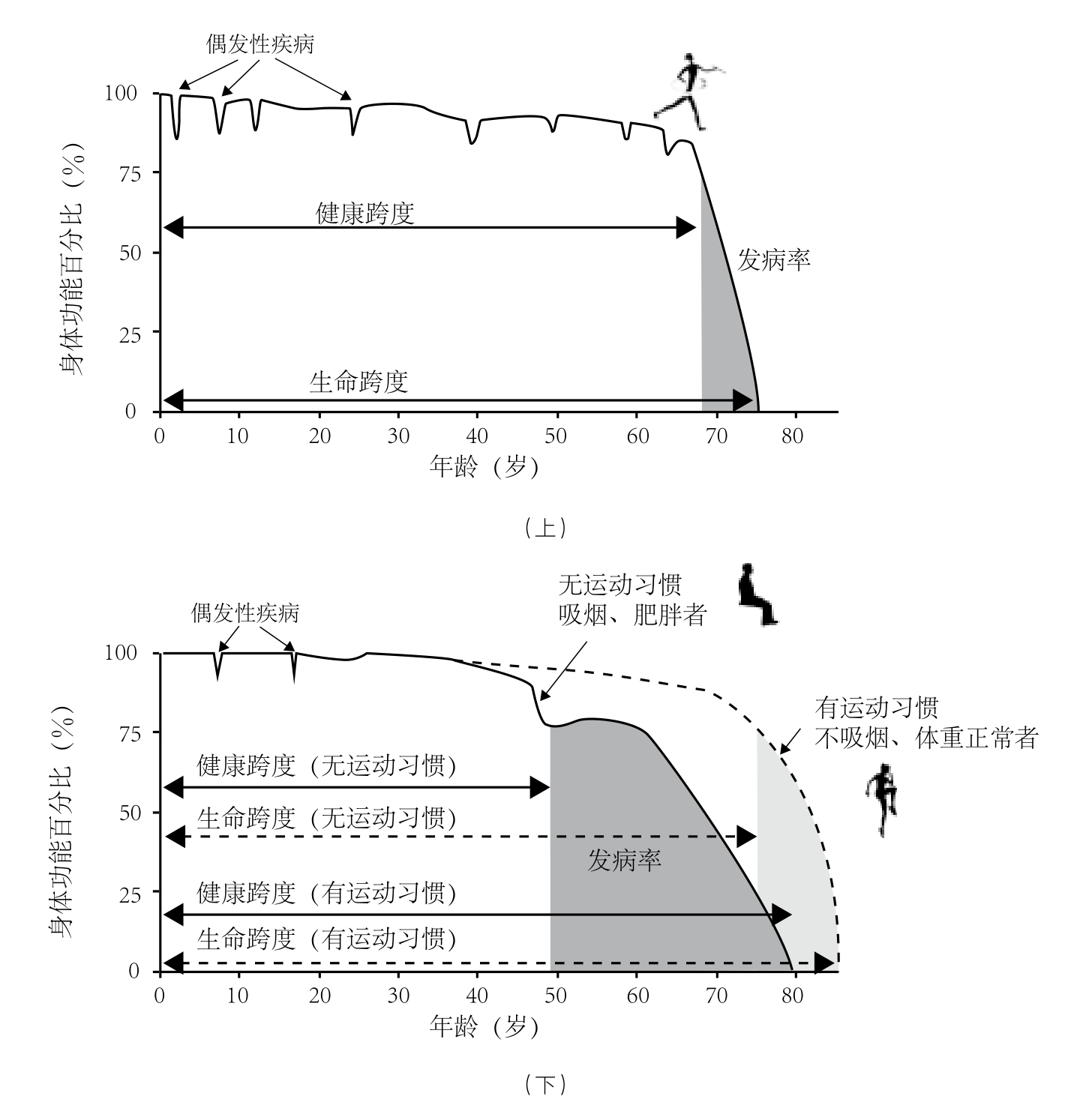

Take a look at the following chart–

The graph depicts the ‘percentage of body function’ of the population - that is, basic health, e.g. if you’re very healthy and have no illnesses, that’s 100% - as a function of age.

At the top are hunter-gatherers. Because of poor medical care, episodic illnesses had a relatively large impact on their health, but their overall health didn’t start to decline significantly until they were about 70 years old. Lieberman once lived with some hunter-gatherers and found that the women among them, until the age of 70, could still maintain a walking speed of 1.1 meters per second, and Lieberman sometimes had to do his best to keep up with his grandmother walking.

In contrast, American women walk 0.92 meters per second at age 50, and by age 60 it has dropped to 0.61 meters per second. The lower part of the graph is even more indicative of the fact that without exercise, the health level of people in modern life drops a step in less than 50 years of age, is relatively stable between the ages of 50 and 60, and then declines markedly from year to year after the age of 60. We live a few years longer than hunter-gatherers, but that’s because we have modern medical care. We actually enjoy significantly less health than they did.

Hunter-gatherers are not only healthy, but they are also in good shape, full of spirit and happy. Compared to them, we are simply ‘alienated’ by modern life.

Where do we fall short? Some people used to wonder if hunter-gatherers ate differently from us. After all, they didn’t have agriculture and didn’t eat as many carbohydrates. There are many advocates of the ‘Paleolithic Diet’, but I understand that the mainstream understanding now is that that makes little sense: hunter-gatherers can live in whatever food system they want, and human eating habits are both broad and variable [1].

- One of the key conclusions of Lieberman’s book is that we are poor at physical activity. *

✵

Hunter-gatherers were physically active for four to seven hours a day, walking 11 km to 16 km for men and 8 km for women. We modern people sit in an office all day, we don’t get much physical activity, we rarely walk, and we are very under-exercised. This is why you need to exercise.

That chart above tells us precisely that with exercise, no smoking, no obesity, and a combination of modern medical conditions, we will be healthier than hunter-gatherers.

So, you say, shouldn’t we also get out and walk for at least four hours a day? Where would I find the time? This is where scientific knowledge has to come into play. It’s okay to compare yourself to a hunter-gatherer, but you can’t do it in a rigid way, you have to know what’s going on. We have to know what the principles of physical activity affecting physical health are so we can treat the symptoms.

- Lieberman’s insight is that the most fundamental principle of everything lies in the body’s distribution of energy. *

The average weight of an adult American man is 82 kilograms. Such a person, if he does nothing but lie in bed to sustain his life, will also consume 1,530 calories of energy per day - this is called the “basal metabolic rate” (basal metabolic rate). If the person is not lying down but sitting, but also doing nothing, resting, then the daily consumption is 1700 calories - this is called “resting metabolic rate (resting metabolic rate)”. Of course the average person doesn’t lie or sit all day, and our average life, under normal circumstances, consumes a total of about 2,700 calories per day.

Do you see the point? This means that our body uses almost 2/3 of its energy for basic body functions rather than for exercise. Only 1,000 calories of your daily energy is used to do various movements. This includes all movement. Getting up from your chair to casually walk around, pick up something, or even talk is movement.

That means that even if you don’t intentionally exercise, your daily activities are already some kind of “exercise”. In fact, what hunter-gatherers call activity is often just sitting around, doing manual labor and talking.

In proportion to their body weight, hunter-gatherers have a basal metabolic rate not much different from ours. They also don’t spend a lot more energy on exercise than we do. The detailed accounting goes like this, we have to categorize exercise into light activity, moderate intensity activity and vigorous activity-

Light activity includes the smallest activities like walking around indoors, which is about 5.5 hours a day for our average adult, and closer to 4 hours for hunter-gatherers;

:: Moderate-intensity activities include brisk walking and jogging, which is only 20 minutes a day for us and 2 hours for hunter-gatherers;

:: Vigorous activities such as breathless sprinting runs, which take less than 1 minute a day for us and 20 minutes for hunter-gatherers.

That’s not a big difference! One of the real differences is between moderate intensity activity and vigorous activity.

Taken together, you only need to add an hour or so of moderate intensity activity and vigorous activity per day to meet the hunter-gatherer standard of exercise energy expenditure. In fact the amount of exercise can be even less if it’s just for your health, more on that later.

So the good news is that we don’t have to spend a lot of time exercising.

But the bad news is that we’re really bad exercisers. *

✵

Going back to Lieberman’s insight, the human body distributes its energy in five ways-

growth, which is when a child grows into an adult;

life support, or resting metabolism, which includes a variety of automatic body repair processes;

energy storage, mainly in the form of fat, i.e. making people obese;

exercise;

reproduction, such as pregnancy and birth control.

These five areas are in a trade-off relationship with each other. Children need a lot of energy to grow, then they won’t use that energy for reproduction; if you climb a mountain all day today, it’s true that you won’t gain fat, but your body’s repair function has also been temporarily terminated; if you diet and reduce your energy input, then you won’t want to exercise, and that’s not conducive to reproduction either.

Hunter-gatherers have a more plentiful life in general, but they also get underfed more often than not. So our bodies are factory-set to be energy efficient: we’re not athletic. No gathering hunter-gatherer is going to have nothing better to do than go out and run around by themselves.

In fact humans are less inclined to strenuous exercise than other animals because we are a high energy user. We don’t fight like lions and leopards, and we have to track our prey for long periods of time in order to get a bit of meat. Our brains are particularly energy-intensive. We give birth twice as often as chimpanzees. It’s like a person who earns more money but spends more on daily expenses; he has to be able to save money to live well.

The way we save money is by not moving when we can. Laziness in exercising is also a factory setting for our bodies.

Yes, there are some runners who are really “in love” with running, and it gives them both physical and mental pleasure - called “runner’s high” - but that’s only if you’ve participated in a race. -But that’s something you have to have been running for a long time to achieve. I don’t know that the hunter-gatherers were also able to run without running. No one is born with a love of running at all.

The paradox is that on the one hand, the body demands that you move a lot, and on the other hand, the body demands that you don’t love to move.

Hunter-gatherers are forced to move by life; they don’t feel this contradiction. You, on the other hand, must resolve to exercise.

✵

So, you make up your mind and say I’m going to exercise. Then here comes the second piece of bad news: *The results of exercise don’t show up that easily. *

The most common purpose that motivates people to exercise is to lose weight, but does exercise really lose weight?

If you take 10,000 steps a day, you’ll walk about 8 kilometers, you’ll burn 250 calories, and you’ll burn off a little fat for it. But note that exercising will make you hungry. And you get that 250 calories back just by eating an extra piece of cake. If you don’t eat that piece of cake, you’re just hungry and tired, and you’re going to interfere with your work and rest.

One study divided some overweight people into two groups, the first group walked briskly five times a week for a total of 150 minutes, and the second group doubled up and walked briskly for 300 minutes a week. Both groups had unrestricted diets. This amount of exercise is already considerable for the average person. But after 12 weeks, the 150-minute group had lost almost no weight, and the 300-minute group had lost an average of only 2.72 kilograms per person.

This is why some people think exercise doesn’t lead to weight loss. But Lieberman thinks it’s just fine, and the long-term effects are pretty big.

But either way, it seems we shouldn’t expect too much magic from exercise. Let’s talk about the real benefits of exercise and how to do it in concrete terms in the next talk.

Notes

[1] Ferris Jabr, Why the Paleolithic Diet is Unreliable? Nutshell, https://www.guokr.com/article/439349/

Highlight

The hunter-gatherer lifestyle determines the factory settings of our bodies. We are unhealthy by poor physical activity. And the underlying principle that physical activity affects physical health lies in the body’s distribution of energy.

- the good news is that we don’t have to spend a lot of time exercising.

- The first bad news is that we really don’t like to exercise.

- The second bad news is that the effects of exercise are not so easily visible.