Prime Doubt 7: Regulating Brains with Noise (End)

Primary Doubt 7: Conditioning the Brain with Noise (END)

Let’s finish Tim Palmer’s book “Prime Doubt”. One of the great joys of learning is when you suddenly realize that two things that might have seemed unrelated are actually the same thing, that they have the same principle behind them.

A key element of Palmer’s book is noise - that is, artificially added randomness. Previously, we added noise to weather models to make predictions, and it can be a huge savings in arithmetic, it can quickly find all sorts of possible outcomes, and it can predict the probability of, say, a hurricane occurring. Noise that can be used as a substitute for sophisticated computation.

In this talk we are going to say that the human brain is a machine that can compute with noise.

✵

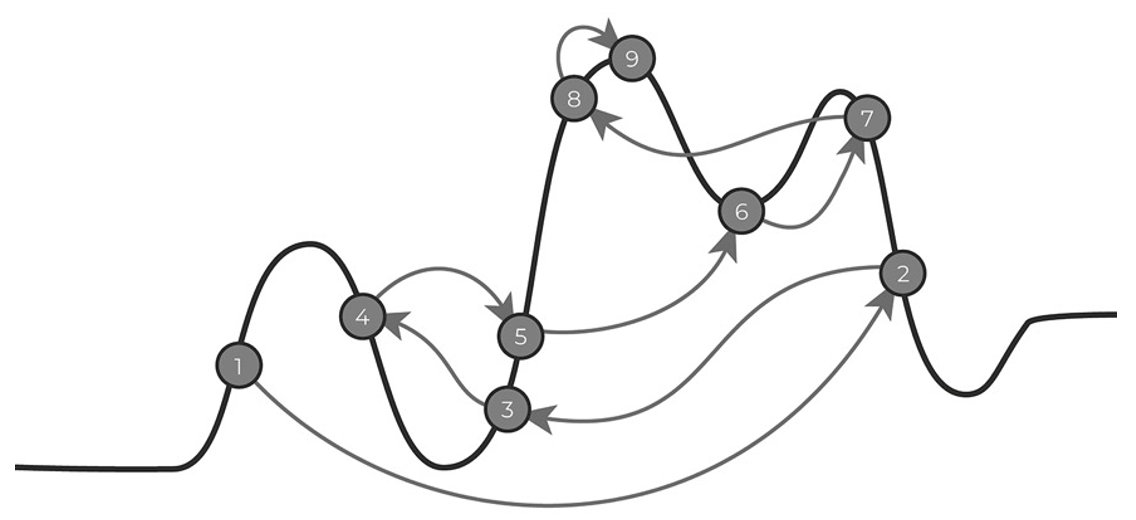

Let’s start with an algorithm question. Imagine you’re probing a mountain road with uphill and downhill slopes, peaks and valleys. Your task is to find the highest possible hill on the path in the least number of steps and stay there. The thing about this game is that you don’t have to walk: at each step, you either choose to jump from one point on the map to another; or you choose to report a random point and let the system tell you what the height of that point is. May I ask what kind of jump you would use?

The intuitive way would be to check the height from position to position along the road, left to right, which would be too slow.

An intuitively faster algorithm would be to start by picking a random point, use that point as a base, move one step to the left and one step to the right to see which side rises, then move in the direction of the rise and move on to probe the next point. If you find that both sides are lower than here, then you’ve found a high point. The problem with this method is that you can easily get stuck on a localized peak and miss higher mountains.

There’s a particularly good algorithm for this called “Simulated Annealing “. Imagine you’re at point A on a map, and you know the height of point A. Now choose a random mountain that you’ve never been to before. Now randomly choose a point B that you haven’t visited before, and if point B is higher than point A, you jump to point B. If point B is lower than point A, then you have two choices-

If it’s still early in the probe, then you jump to point B with a relatively high probability. This is because the map still has a lot of uncertainty for you, and the probability of you randomly jumping to run into a higher point in the future is high;

If it is already in the late stages of detection, then lower the probability of jumping.

In fact, this process is very much like looking for a job and jumping: if you don’t know much about the industry yet, you can jump if you have about the same chance; if you already know the industry very well, then you have to see a higher salary before jumping.

Why is it called a simulated annealing algorithm? Because it’s like a piece of red-hot iron, very hot at first, it’s softer and easier to make changes; as time goes by, the iron slowly cools down, it hardens, and it’s not easy to change. The longer the time, the colder the temperature, the harder the iron, the less you love to change.

If we imagine random jumps as noise, then the process of annealing is a process of less and less noise and more and more focused action.

The simulated annealing algorithm proved to be a very efficient detection method. This algorithm gives us three hints.

First, acting in a step-by-step fashion, scanning one by one in a fixed direction, is a very inefficient way to detect;

Second, actively incorporating randomness can quickly help you find a better way out;

Third, use randomness in a controlled way: early on, you can randomize a little more, then gradually reduce the randomness, and later on, your actions should become more and more defined.

- Combining randomness and direction in this way is a good way to solve problems. *

✵

As you’ve probably already thought, isn’t that what creative thinking in the human brain is all about, divergence before concentration? We never solve math problems by taking all the problem solving techniques we’ve learned and putting all 18 weapons on the table to try them out one by one, that’s too slow. We tend to let our minds jump around first, sometimes jumping right to find the idea directly.

The same is true of ‘eureka moments’ when scientists make major discoveries. For example, Roger Penrose was walking and chatting with a coworker on his way to work one day, and when he waited to cross a street, the two of them paused in their conversation, paid careful attention to the cars, crossed the street and continued to talk, and then he separated from his coworker. It was at this point that Penrose suddenly felt an inexplicable sense of elation! He felt as if something good had happened, but he couldn’t remember what it was.

So he began to recall, from what he ate for breakfast all the way back to the moment he crossed the street …… He suddenly realized that when he crossed the street just now, he had generated an idea that could be used to solve the problem of the spacetime singularity that he had been thinking about lately. He hurriedly wrote it into a paper.

This paper, published in 1965, later helped him get the Nobel Prize in Physics.

There are so many stories like this one. For example, how did Zhang Yitang come up with the key step in solving the twin prime conjecture? He was playing at a friend’s house that day, and the friend asked him to go to the backyard to see if any deer had walked in, and as soon as Zhang Yitang arrived in the backyard, inspiration suddenly struck him.

Wiles, the mathematician who proved Fermat’s Great Theorem, has a special summary of this, saying that the solution to the problem has to be in three steps–

*First step, you must first be very focused all the time to think about the problem, to think clearly in all aspects;

*Step 2, stop, relax, relax, do not deliberately think about the problem for the time being. This is when the subconscious mind takes over ……

*Step 3, and maybe at some point, inspiration will suddenly appear.

In fact, this approach may have been known to you for a long time, our column has talked about it before.

However, Palmer offers a very interesting explanation for this mode of thinking in his book.

✵

We know that Daniel Kahneman famously called it System 1 and System 2 in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow.System 1 is effortless, fast, automatic thinking; System 2 is slow, logical, highly focused thinking like solving a math problem.

Palmer says that if you look at the power consumption of the brain, regardless of whether the brain is in System 1 or System 2, it’s consuming 20 joules of energy per second, the equivalent of a 20-watt light bulb. So what’s the difference between System 1 and System 2?

When the brain is in System 1, the energy consumption is spread out over several tasks, you’re doing several things at the same time, and each thing gets a lower power of thought. Whereas when the brain is in System 2, all energy consumption is focused on one task. In this way, System 1 and System 2 can also be called Low Power Mode and Power Dense Mode.

At the level of the brain’s hardware, there are significant differences between these two modes: *Power affects the precision with which neurons transmit signals. *

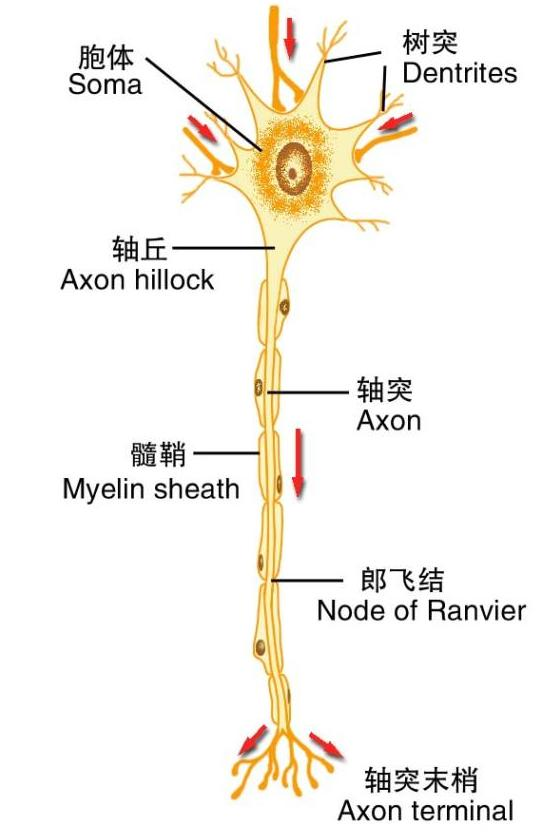

The diagram below shows a brain neuron -

A signal is sent from the cell body and has to travel through a long axon to get to the axon endings. If an electrical signal is transmitted directly, it dissipates on the way. To ensure that the electrical signal is transmitted accurately, it must be amplified continuously by several “Langfeld junctions” on the axon. These Langfeld junctions are like protein transistors.

But amplifying signals requires energy. If the brain is in System 1, a low-energy mode, specific neurons don’t get much energy, and signals are lost in transmission, resulting in noise.

But as we said earlier, noise doesn’t have to be bad. Noise can make the mind jump and can give you inspiration …… That’s why it’s easy to get inspired when you’re in multitasking mode and your mind is distracted.

In fact, the brain can’t get away from noise at all. It’s impossible for every neuron to transmit signals accurately, there’s not that much energy available. You usually look at a picture, or watch the view out the window, never pixel by pixel, your neurons have done the rounding, filling in the gaps with lots of noise. We use noise all the time.

But if you’re in low-power mode all the time, not concentrating at all, you’re not going to achieve anything. New ideas come to you and you still have to filter it, keep the good ones, drop the bad ones - as you think about it more and more, you lean more and more in a certain direction, and the noise gradually decreases and the signal gradually strengthens, as if it were a simulated annealing algorithm, and you get firmer and firmer.

In the old days, we used to say in brain neuroscience terms that this is how the brain has to rapidly switch between a ‘default mode network’ a ‘salience network’ and a ‘central executive network’ thus generating creativity. And here Palmer explains the underlying principle in terms of energy consumption and noise.

Noise has a deeper meaning.

✵

None of the noise in a weather model is generated by its native algorithm; the noise is imposed externally by the researcher. For the simulated annealing algorithm, the noise is added with a random number generator. To the brain, noise is something that can’t be controlled entirely with your mind.

Simply put, because of noise, our brains are not fully algorithmic.

Note that this is a very powerful and very controversial insight. There is no noise in a normal computer program, it always executes your instructions exactly. Of course you can add random numbers, but random numbers at the software level are “pseudo-random numbers”, still generated by the algorithm, and cannot be considered noise.

Palmer here says that the brain, on the other hand, has real noise.

Note again that this is not to say that the brain is intrinsically indeterminate - Palmer argues against the intrinsic indeterminacy interpretation of quantum mechanics - it is simply to say that the behavior of the brain cannot be described by an algorithm. Just as there is no orbital formula for a three-body system.

The brain is, by nature, a chaotic epochal thing.

The idea that the brain is not entirely algorithmic is at the heart of Penrose’s famous book, the one called The Emperor’s New Brain. Penrose says that if the brain were entirely a machine executing a particular algorithm, it would not be able to transcend Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, and it would not be able to appreciate that which “cannot be proved mathematically, but which can be perceived to be right”.

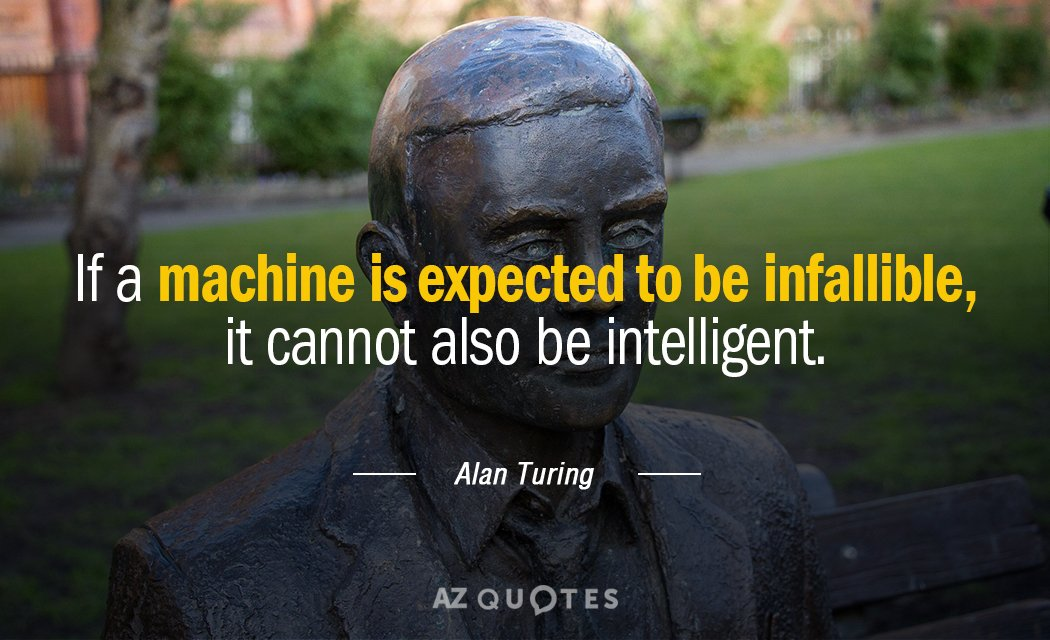

Alan Turing, the father of computer algorithms, also famously said: * A machine cannot be intelligent if it can never make a mistake. *

It’s the noise that allows our brains to outperform algorithms.

- It’s your leaps of thought, your wandering and slipping, your daydreaming, your vague inability to remember what you’ve just seen, and your sparse daring to accept ideas that aren’t rigorous that make you a human being and not a machine. *

But that’s not to say we’re fundamentally different from computers - after all, you can add noise to computers too. Palmer then suggests that AI shouldn’t be all algorithms either, but should also actively add some noise. He suggests that in the future, computers could use two types of chips, a traditional deterministic chip, and another chip that is deliberately lowered in power so that the chip itself carries some noise for fuzzy computations ……

I bet Palmer didn’t use the GPT-3. there is no need for any special chip at all, the GPT-3 can just add noise.

✵

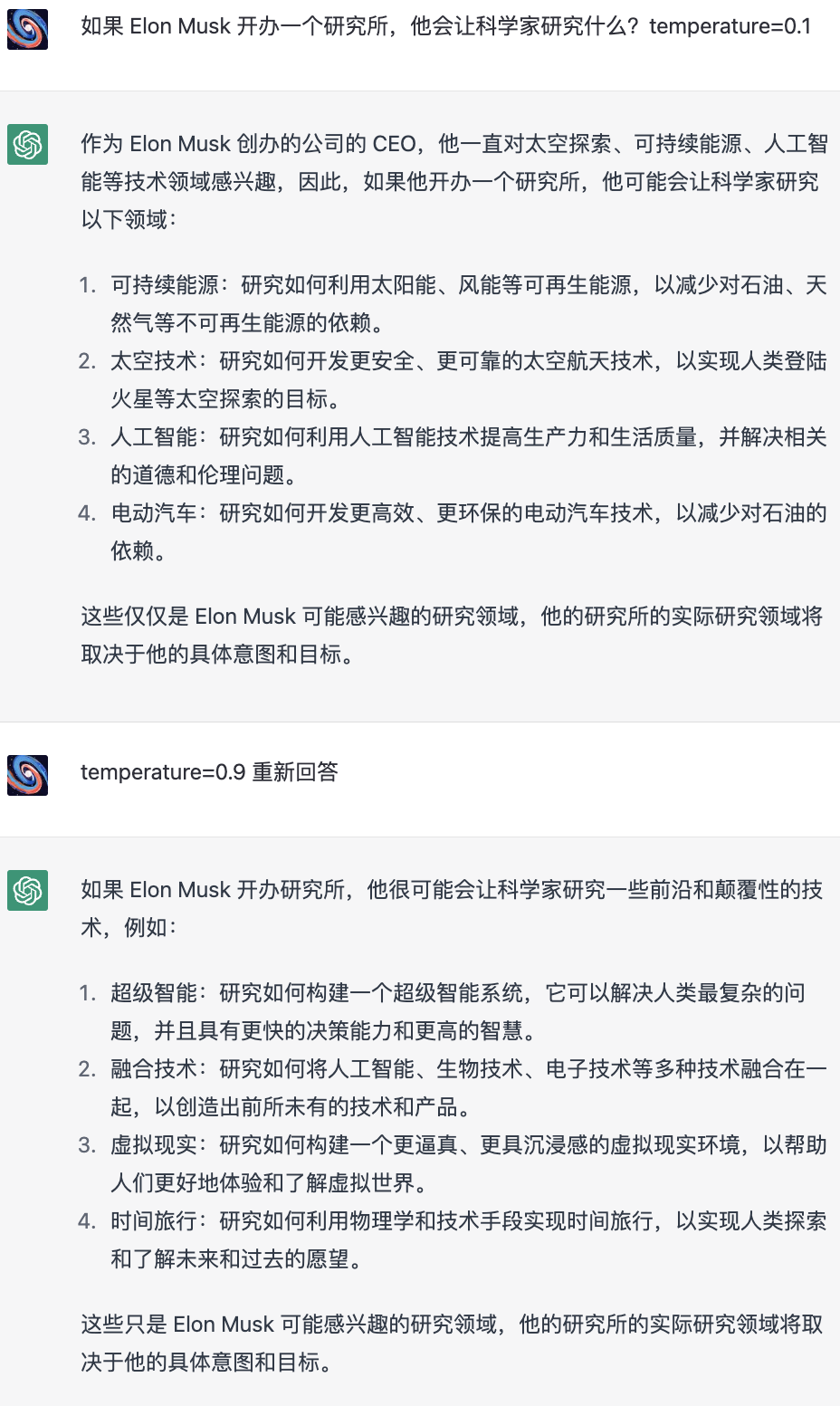

For example, ChatGPT, which a lot of people don’t realize, you can set its temperature value. Temperature is a number between 0 and 1. Higher temperature means more noise and randomness. With a low temperature, ChatGPT outputs by-the-book, middle-of-the-road, not-so-imaginative answers; turn the temperature up, and it will output brain-opening answers.

For example, I asked ChatGPT, if Musk were to start an institute, what would he have scientists work on? I first set the temperature to 0.1, and ChatGPT answered that Musk has always been interested in space exploration, sustainable energy, artificial intelligence, and other technological fields, so he might start an institute to let scientists study sustainable energy, space technology, artificial intelligence, electric cars, and other fields.

This answer sounds reasonable, but overly reasonable and a bit unimaginative.

Then I changed the temperature to 0.9 and asked ChatGPT to re-answer. This time it came up with some cutting-edge and disruptive technologies, saying that it might be working on “super-intelligent fusion technologies”, virtual reality, time travel, and so on.

Look how nice this feature is, you can adjust the size of the AI brain by temperature! Wouldn’t that be more convenient than a human brain?

✵

I don’t think noise says anything fundamentally different about human brains and computers. After all, computers can bring their own non-algorithmic noise, and as Palmer says can tinker with the hardware. In fact today’s computer chips originally had a physical random number generator on them.

But if the computer can often interact with you in ways you don’t expect, you’ll be more likely to think it’s alive. You can also give yourself more noise, more brainstorming, and creativity if you want to have a higher presence at work, and you’ll feel more like a person than a machine.

Palmer ends the book by trying to explain human consciousness, free will, and religion with his ‘invariant set’ theory, which I felt was overly far-fetched and not graceful. I’m not a big fan of that theory, so let’s leave it at that.

But the ones I’ve talked about - with the exception of Palmer’s new interpretation of quantum mechanics - are still pretty solid.

(The End)

Get to the point

It’s the noise that allows our brains to outperform algorithms.

It’s your leaps of thought, your wandering and slipping, your daydreaming, your blurry memory of what you just saw, and your thinly veiled daring to accept ideas that aren’t strict, that make you a human being and not a machine.