The Way of Harmony (below)

The Way of Harmony (below)

According to Kenichiro Mochizuki, the Way of Wagamama allows you to find a sense of peace in whatever you do in life; and at the social, political, and corporate levels, Wagamama puts together ingredients that seem to be contradictory and unlikely to go together, and achieves harmony.

Kazami has shaped the Japanese character to a considerable extent. Also entrepreneurs and celebrities, Americans are high-profile and flamboyant, expressing their opinions everywhere and pointing out their views on Twitter, while Japanese are low-key and introverted: polite and reserved when they succeed, decent and polite when they fail, and seldom express their opinions publicly.

If you spend a short amount of time together, you might think that Japanese people are insubstantial and have no true character - but behind this silent, reserved character of Japanese people is nagomi, a way of surviving in a high population density society.

✵

Comparing different cultures together is interesting in itself.

There was once a German who visited Japan and Kenichiro Mochizuki chatted with her, saying that Japanese office workers usually find an izakaya after work, where they drink while pouring out their grievances to each other, spouting off about their bosses, sharing their woes, releasing their stress, and also cementing their personal relationships. The Germans were surprised to hear that this would never happen in Germany! The German company is a competitive relationship between the employees, how is it possible to drink while exposing their weaknesses, but also say bad things about the boss?

The main point is that the Japanese work and life of these two seemingly contradictory things to “and see”: employees to the company as a home, the company also like to take care of family care of employees, we talk about unity, the relationship is very comfortable, not like the German sense of isolation.

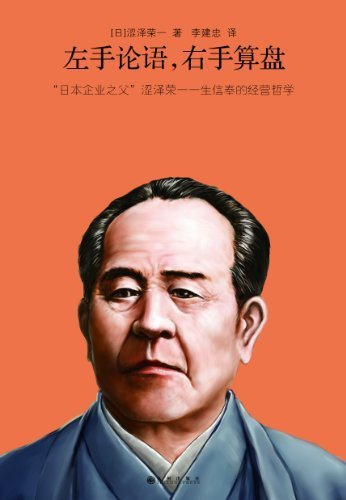

On a larger level, this wazumi also includes the idea that a company is not just about making money. Eiichi Shibusawa, the “father of Japanese capitalism” and a great industrialist from the end of the Edo period to the Taisho period, wrote a book called “Left Hand Discourse, Right Hand Abacus,” which emphasizes the social responsibility of entrepreneurs.

Eiichi Shibusawa founded many companies, with businesses ranging from banks, hotels, beer, mail ships, and even the Tokyo Stock Exchange …… But he also established a university, founded the Japanese Red Cross, and engaged in public service. Eiichi Shibusawa’s philosophy was that the purpose of a private company was not to maximize profits, but also to work for the welfare of its employees, its customers, and society as a whole. The Japanese embraced his philosophy.

If you ask Americans, many economists believe that the mission of a company is to maximize the interests of its shareholders …… Nowadays, some people in Japan also say this, but this statement has never taken hold in Japan.

✵

Japan’s politics are also different from elsewhere. Japan is a multi-party democracy, but from the end of WWII to today, Japan has been ruled by the LDP for the vast majority of the time, it’s almost like a one-party system. So do you think this shows that Japan’s democracy is still very immature? Is it that the LDP is engaging in autocracy? It doesn’t seem so.

Kenichiro Mochizuki said that the LDP has actually been engaging in pull politics - pulling in the opposition parties.

There are rumors that the Chief Cabinet Secretary of the LDP has a secret fund of $1 million a month, which is specifically used for pulling strings with the opposition parties. This pulling of strings means not buying, but listening to opinions and balancing interests. Although the opposition parties could not come to power, they would privately collude with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) on their demands and ideas, which included requests for improving social welfare and raising the minimum wage level, which were beneficial to the people, and the LDP would listen to these views. Therefore, although the opposition parties are not in power, they have been participating in politics, and they have actually played a role.

By Western standards, this kind of private collusion is corruption. But if you look at it from the point of view of “whether or not the interests of all parties have been successfully compromised”, you can also say that it is a consultative democracy.

It’s the nagomi of politics: although there are conflicts between parties, we don’t have to fight to win or lose. You’re against me, but if I can fulfill your demands, maybe you don’t have to throw me out of office.

The two-party system in the U.S. is such that nearly half of the voters feel defeated and abandoned in every election, and the political conflict in Japan is more subdued. Citizen protests and demonstrations, which are common in Western countries, are rare in Japan. But you can’t say that Japan is dead in the water without social change, it’s just that the Japanese seek to change in incremental ways.

It is true that Japan does not have the same degree of political freedom and freedom of speech as the West, but this does not mean that Japanese society cannot accommodate different voices. Differences of opinion and position are more often negotiated, avoiding confrontation and minimizing open hostility.

Japanese politics and see also manifested in Japan does not have a “dominant” ideology. Japan does not say that it must be guided by any ideology, and does not engage in purely liberal or conservative governance. This is actually very rare, because Japan is a mono-ethnic country, if we all think the same way, it is easy to go to the extremes. …… Perhaps modern Japan has absorbed the lessons of the former militarism, and the society is able to accommodate a diversity of ideas.

Just think about this fact: when Japanese people get married, they generally have Christian-style weddings; but funerals, generally, are Shinto. Isn’t it a remarkable achievement that two such different religions have been able to coexist graciously in one society?

✵

Why is it that Japan loves to make everything into a ‘Do’? For example, Judo, Kendo, Shudo, Tea Ceremony, Flower Ceremony …… To us Chinese, it is obvious that these Tao are more form than content. For example, the tea ceremony, in order to drink a tea, a variety of steps are incredibly complicated, simply scroll, and then cook out of the tea is not very good, which in the end what is the meaning of it? This formalism is not posturing?

This involves a unique way of thinking of the Japanese people, that is, they love to dig the “spirit” of a thing to the extreme …… We will have the opportunity to talk about this later. In Kenichiro Mochizuki’s view, these are the embodiments of wakizashi: * It is the combination of the technique itself and the spiritual inculcation of the person. *

You don’t learn a skill just to learn the skill itself, but also to enhance your spirituality through that skill.

For example, if you learn judo, you don’t just learn it to beat your opponent or to strengthen your body, but you also learn it as a spiritual practice and growth. Judo has rules beyond technique, moral requirements, and most importantly, philosophical thinking. Every time you train, you must first enter a state of sincerity and respect for the teacher, who may give you “value”.

I think it is precisely because of the spiritual output that these “ways” continue to grow today. Otherwise, the modern world is so advanced that martial arts can’t beat a pistol, making tea doesn’t necessarily beat Starbucks in a double-blind test, and those traditional things would have been eliminated long ago if they didn’t have spiritual value.

The reality is that simply engaging in pragmatism is pretty tedious. Just as some entrepreneurs earn money to ponder art, they collect art is not all for appreciation, but also in the enrichment of spiritual life.

✵

We know that the Japanese appreciate cherry blossoms almost to the extent of being obsessed with them, very spiritualized, what’s it like?

Kenichiro Mochizuki says that cherry blossoms are characterized by the fact that they will definitely bloom every year, but exactly when they will bloom and the length of their bloom period is uncertain. If the weather is warm, the flowers bloom easily; however, if the weather is cooler a few days after the flowers bloom, the flowering period can be longer. However, if it rains or is windy, the cherry blossoms will fall to the ground prematurely. In the best case scenario, the cherry blossoms last only a week.

It’s short, uncertain, and beautiful. The Japanese consider it to be like human life. Aren’t such things worth marveling at?

There’s an element of Japanese culture called “object mourning,” which laments the transience of things - and yet Japan is home to some of the oldest things in the world.

Japan has family companies that have been passed down for hundreds of years. Japan’s Ise Jingu Shrine has been rebuilt and relocated every 20 years for thousands of years. Japan’s current emperor is the 126th emperor.

- Realizing the transience of things, but having a way to keep it passed on is a form of wazami. *

There is also wazumi between life and death. The Japanese believe that people don’t really disappear when they die; as long as you remember them, they still exist. The key setting of Shintoism is that people become gods after they die. Important figures in Japanese history are worshipped as gods by the people, and even unimportant figures, including those who have not left their names, may become important gods.

Amaterasu Omikami, enshrined in the Ise Jingu Shrine, is the highest-ranking kami in Japan, but people have forgotten what she was or what her name was when she was alive: they only remember that she was once a wonderful woman.

✵

Finally, let’s talk about Japan’s creativity. Japan has clearly not kept up with the information technology revolution since the 1990s. Japan is clearly lagging behind the US, China, and South Korea in hardware, software, internet applications, and AI, which may also have something to do with Japan’s stagnant economic growth over the past three decades. But Japan still has a high level of innovation in many other areas.

The focus here is on culture, such as anime. Japanese anime is deeply influenced by Disney. However, Japanese companies have low budgets and can’t draw as detailed as Disney, and the number of frames per second is relatively small, so it looks a bit raw. But this has become a specialty. Japanese anime doesn’t fight for technology, so how come it’s also popular all over the world?

I think the key to innovative soil is freedom: no license is needed here, you can do whatever you want, however you want to do it, and the people can naturally invent good things out of it. Japanese society is originally strict, but it is very lenient in terms of animation innovation.

Unprofessional, low level, young and immature works are acceptable to the Japanese. And the Japanese cultural community has also played a special role in specializing in advocating immature, young, relaxed things aesthetic orientation, that is, “kawaii” - that is, cute.

In Japan, everything is kawaii. It doesn’t matter if it’s high culture, low culture, powerful, powerless, men, women, young and old, even if you’re a tough guy Schwarzenegger and you come to Japan to shoot a program, you can be kawaii.

And as long as you are kawaii, even if you are new and strange, society can quickly accept you. *Kawaii is the combination of the familiar and the unexpected. *

Anime and manga capture this. Anyone can draw manga, regardless of whether it’s elegant or vulgar, and regardless of whether they’re a novice or a veteran. That’s why manga is so popular in Japan.

The father of Japanese anime is Osamu Tezuka, who created a series of works, including “Astro Boy with Iron Arms”, which brought joy to countless children, so how did he come up with the idea of drawing manga?

Near the end of World War II, the Japanese mainland was a scorched earth after being heavily bombed. Osamu Tezuka happened to have a long trip home on foot, and he was greatly touched inwardly by the war ruins he witnessed on the way. But instead of trying to get into economics, he thought that the Japanese were so traumatized that they needed to be comforted by manga, so he started creating manga.

Ruins and manga are two very contradictory things, and this is Osamu Tezuka’s Kazumi.

Many people in the West believe that geniuses are unique, while the Japanese believe that * Genius is just a connector of the world - creation is not something that a genius imposes on the world, creation is just something that a genius forms by organically blending various things in the world, including blending himself with the world. *

✵

It is not true that all countries should follow Japan’s example or use Kazami for everything. The most obvious disadvantage of Kazami is its inefficiency. In the face of all kinds of conflicts, sometimes you just have to dare to stick to one end in order to solve problems quickly. Practices like the Japanese employees who call the factory home and companies that don’t like layoffs are doomed to be less efficient than American companies.

But sometimes low efficiency may be the price of harmony, sometimes you don’t have to have the highest efficiency …… Maybe these two lectures can let you know more about Japan.

As individuals, how should we practice nagomi?

Kenichiro Mochizuki suggested in an interview [1], * Go for the opposite. * No matter what you do routinely every day, you can find one opposite thing to do along a diagonal direction -

If you work indoors from morning to night, you need to get outside and run;

If you always drive to and from work, you need to walk;

If you’re always with family and familiar friends, you need to get out and meet new people - conversely, if you’re surrounded by strangers all day, you need to spend more time with family and friends ……

In a nutshell: * Kazumi requires you to add some opposites and contradictions to your life, blending them together to form harmony. *

I don’t think the Chinese sages would have objected to any of this. In the perspective of ancient wisdom, it’s really easy for modern society to polarize people.

Annotation

[1] Kevin Dickinson, Nagomi: The Japanese philosophy of finding balance in a turbulent life, bigthink.com, APRIL 27, 2023.

Highlight

The Way of Nagomi enables you to find a sense of peace in whatever you do in life; and at the social, political, and corporate levels, Nagomi puts together ingredients that seem contradictory and unlikely to go together to achieve harmony.

How should one practice nagomi? Go for the opposite. Wagomi asks you to add some opposing and contradictory elements to your life and blend them together to form harmony.